Viviane Faver

New York City is the birthplace of hip-hop. Fifty years on, the artistic movement now spans the globe. I have the pleasure to interview Hip-Hop Pioneer Ralph McDaniels and talk about Music and NYC. From the start, music videos have been essential in hip-hop’s ability to penetrate NYC culture and become a global phenomenon. Videos allowed different expressions of hip-hop to be front and center—fashion, hair, dance, graffiti, and design—providing insight into the culture as it developed in real-time.

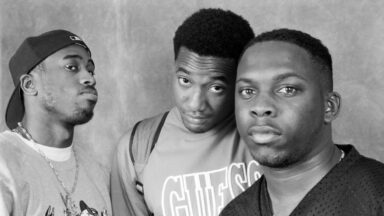

Ralph McDaniels was one of the earliest pioneers in the medium. “Uncle Ralph,” as he is affectionately known, rooted his career in the visual elements of hip-hop with one of the earliest music videos shows on-air, Video Music Box.

He also directed and produced groundbreaking videos from artists such as Nas and Wu-Tang Clan. We recently spoke with the multitalented VJ about his early days, favorite eras in hip-hop, and most memorable on-air interviews.

TellTell us about your New York City upbringing.

Ralph McDaniels: I was born in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, spent some time in Flatbush, [Brooklyn], and moved to Queens Village. That’s where I grew up.

My family is from Trinidad. Many people in hip-hop have a Caribbean background—from the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Jamaica, Trinidad, Barbados. The first time I went to Jamaica I was shooting a music video, and it amazed me that everywhere I went everyone had speakers blasting music in front of their home, just like hip-hop fans did.

Where did some of NYC’s biggest hip-hop moments happen in the ’80s and ‘90s?

RM: The Ark was one. We used to do these parties on Beverly Road near Flatbush Avenue. The first time Mary J. Blige or Diddy did anything in Brooklyn was there. LL Cool J, Fugees, Wu-Tang. I was bringing artists to the community. It was ushering in a time that we didn’t always have to go to Manhattan for big-name events. It was important for artists to reach fans where they were in their boroughs.

There was the Tunnel, at 27th Street and the West Side Highway. Funkmaster Flex (radio host and DJ), Chris Lighty (music industry executive) and Jessica Rosenblum (nightlife promoter) put that place on the map. It was one of the spots that you could see hip-hop in its purest form.

The Palladium on 14th Street. There were some iconic performances here—Jay-Z and Biggie [who performed together at a fashion show in 1996]. Now I believe it’s an NYU dorm.

In the 1980s, hip-hop came from the Bronx and ended up downtown Manhattan. Sugar Hill and all those artists from that era ended up performing at the Roxy. That was where Basquiat and all those people in the downtown arts scene were mixing with hip-hop, where art and music collided.

You began your show when it was hard to do something independent of a major network. How did you pull it off?

RM: I started Video Music Box in 1983. I got the idea when I was working as an engineer for a local, municipal New York City TV station [WNYC-TV] fresh out of college. They had a fire department show, an NYPD show, a housing department show. Looking at all the monitors, I thought, “I would like to see something on these channels that I was interested in.”

There was no such thing as music videos back then. MTV started in 1981, but no one really saw it because not many people had cable. This is a time when there were antennas on the TV to get reception.

Some videos came into our studio of R&B artists performing. It wasn’t meant for TV, just for us to become aware of who these artists were. I thought, “What if I played these on TV and talked over them?” I was already a DJ, so I knew how to play music and talk over it—I figured I could do the same with videos. The station told me to plan out what I wanted to do. And that’s how Video Music Box came to be.

From early on in your show you were interviewing big artists. How were you able to make that happen?

RM: Personal relationships. I was a pretty popular DJ in Brooklyn and Queens. Because I went out to the clubs, album-release parties and networking events, I had the opportunity to talk to artists directly. I would tell them about the show and invite them to the station or meet them wherever they were performing that night. So I built this one-on-one rapport with some of the biggest names in hip-hop.

They weren’t getting the same publicity that pop artists were getting, so they were happy for the exposure. As time went on, they knew who I was because they were watching the show, so it got easier to book artists.

Could you see the potential for superstardom early in artists’ careers?

RM: Nas says I have the ability to see that somebody is hot before it happens, no matter what genre.

With Lil’ Kim, for example, she changed everything. First of all, she was a part of Notorious B.I.G.’s camp, and it was clear that anything that he was a part of was going to be a success. But the way she dressed and her whole persona was just different. Before her, you never really heard a woman curse in hip-hop. Guys were like, “Hey, you can’t say that,” and all of the women in the club were like, “Yes we can!” She used to be at my parties just hanging out with her friends, so when she became an artist, I already knew who she was.

Bad Boy [Records] was so hot. I knew Diddy from Uptown Records. He was an intern. Actually, he styled a video that me and my partners directed, Father MC’s “Treat Them Like They Want to Be Treated,” and he danced in it. I was paying attention to anything he had going on because I could tell he was going somewhere. He had a pulse on what was happening.

What other music videos have you worked on?

RM: Nas’ “It Ain’t Hard to Tell,” his second single off of Illmatic. Shaggy’s first video, “Oh Carolina,” which we shot right on Flatbush Avenue in Brooklyn. Black Moon’s “Who Got da Props” we filmed in the Meatpacking District when there was nothing much over there. We set up a couple of lights and did it in three hours.

Another popular one I did was Wu-Tang Clan’s “C.R.E.A.M.” I knew RZA back when he was going by the name Prince Rakeem on an indie label [Tommy Boy]. A few years later he said had something new, Wu-Tang, and he showed me a video he created for “Protect Ya Neck.” I played it on my show before they even had a record deal. They kept growing and he came back and sent me “C.R.E.A.M.,” and I was like, “Whoa! What is going on here?” I knew it was something so different. In that video I wanted to take them out of Staten Island because I wanted to show people they were everywhere. So part of that video is filmed in Harlem and part in Times Square.

You’ve seen New York City develop over the years. What is your perspective on hip-hop here?

RM: The thing with hip-hop is it was always underground. That still exists. There are all these gems around NYC that exist that you have to be on the scene or know somebody on the scene to know where it is.

Hip-hop wasn’t allowed in certain places back in the day. But hip-hop is everywhere now. You can’t escape it. That’s exciting. When I started hearing it in sports arenas, that’s when I knew hip-hop made it. I never thought hip-hop would be what it is—but I’m happy it is.

How to celebrate the 50th Anniversary of Hip-Hop in NYC this summer:

- Hip-Hop started in New York City 50 years ago, on August 11, 1973. Celebrations include free concerts such as “Birth of a Culture,” Grandmaster Flash and Friends in the Bronx’s Crotona Park on August 4, and BRIC Hip-Hop 50th Anniversary Weekend on August 11–12.

- Beatstro, the hip-hop inspired Mott Haven restaurant, offers a menu blending Southern comfort and Puerto Rican cuisine. Visit for happy hour from 4–8pm or a Beats n’ Brunch on weekends.

- Join expert dance instructors for free Dance in Times Square Ailey Extension classes, including a hip-hop workshop on June 30 and a Hip-Hop 50th Anniversary Celebration on August 10.

Recent Comments